back

back

Glitch Art is Death

Reptyle,

entroplay,

Nick Briz,

Joana Chicau,

AK OCOL,

Charlotte Lengersdorf,

Bob Georgeson,

Estelle Flores,

Daria Ivans • #fubar_expo • 2024

What is glitch art?

The response I most often give is “Oh, God” so one can only assume that glitch art has divine qualities to it (trust me, it does). For me, step one is to approach it from a purely technical point of view. I find that accompanying my semi-comprehensible ramblings with a quick Google search result for “glitch art” helps people understand what it is best, because most people who have Internet access and a loose interest in art or media, have already encountered glitches one way or another, often by accident. Or luck.

Glitch art is often interpreted through multiple lenses: a philosophy, a community, an art movement, a technique. All of which seem equally correct and wrong. There are a few words that often pop up while discussing glitches: errors, malfunctions, mistakes, failures. None of these words are synonyms for “glitch”, but they seem to live in its proximity, close enough to be interchangeable sometimes and when/if necessary. Sort of like a last resort at explaining glitch art. Those who have been playing with glitches for years tend to avoid them like fire.

What even constitutes a mistake? The Merriam-Webster dictionary describes “failure” as an omission of occurrence of performance, a state of inability to perform a normal function, an abrupt cessation of normal functioning, a fracturing or giving way under stress, a lack of success, and one that has failed. A “mistake” is to blunder in the choice of, to misunderstand the meaning or intention of/misinterpret, to make a wrong judgment of the character or ability of, to identify wrongly/confuse with another.

A fracture, a degradation under stress, stands out among these descriptions as it strikes me as less dry and matter-of-fact than the rest. It evokes the feelings of gradually worsening pain, slowness, and inevitability.

Of course, these are just some descriptions. I won’t be getting too deep into the semantics of it all, because it is literally (and non-literally) not the point. The goal of this text is to paint a bigger picture of what glitch art includes, evokes, and encapsules, and maybe at the end come to some sort of a conclusion on what glitch art could also be among other things. There is a lot to explore here. I’ve always had a lot of admiration for artists working with unusual formats, both in the physical and the digital realm, and I was absolutely delighted by the diversity of techniques and approaches in last year’s fu:bar exhibition. It was oddly satisfying to see how so many of them complemented each other and fit together nicely like pieces of a (glitched) jigsaw puzzle.

Despite glitch art’s elusive definitions, some artworks capture its essence and sensibilities with unmistakable (pun unintended) clarity. “compliant_identity” by a French digital artist and experimental videographer, Reptyle, incorporates multiple techniques and aesthetics that I’d consider signature to the visual glitch experience: databending, pixelsorting, broken files, and error windows. The portraits in this digital collage are rendered faceless as a result of heavy alteration and glitching.

Reptyle’s first glitch creations were a direct result of being submerged in the Internet culture. She began by making oversaturated and deep-fried memes and shitposts and moved on to exploring more in-depth techniques, which eventually led her to finding his own audience and community after the 2023 Glitchtober event. A decade ago glitch artists kept entertaining themselves with debates on how dead glitch art was during its 2010’s raise in popularity in the mainstream media. Every now and then, I like a subtle reminder of how relatively new glitch art is to a lot of people. A breath of fresh air through the use of familiar tools. It gives me a sense of perspective in a way that I think would feel me with a sense of dread ten years ago, but no longer does. While glitches will continue to exist in video art or video games, for new, upcoming generations, a glitch’s artistic use may as well start on the Internet, in brain-rot-fueled abstractions or whatever aesthetic rises in popularity in the future, making way for new nostalgic sensations.

A lot has been written about the sense of nostalgia that glitch art evokes. For a lot of 30+ year olds dabbling in this form of creative expression, their first encounter with glitches happened in their childhoods. Distorted movies, unexpected occurrences in video games, corrupted files. If you had the opportunity to live a fraction of your life online in the late 90s and early 00s, you definitely heard of—perhaps even partook!—in piracy. It was an exciting time. You never knew if the torrent you were waiting for for hours to download was a foreign movie that was unavailable in your country that you were dying to watch or a virus created to destroy your files and siphon out your data. Or, you know, porn. Technology was exciting, computers still relatively new, and the Internet a vast, undiscovered, ungoverned land yet to be conquered by our current web overlords.

My dad is an engineer. Growing up not only did we have a computer with an Internet access (a relatively rare thing for most households in my country in the 90’s), but also an oscilloscope in the same room. Although I was way too young to understand the meaning of my father’s work or how any of his machines operated and for what purpose, I was fascinated by them and greatly enjoyed the sounds and visuals of an oscilloscope. To me, “Oscillonet” by entroplay (Armon Naeini) presents a clash of two worlds.

The artwork is an analog oscilloscope hacked to serve as a functional web browser. While hacking hardware for the sake of repurposing it as an Internet browser is impressive in itself, “Oscillonet” adds one more layer to this experience allowing the user to essentially listen to what the Internet sounds like. I’ve always enjoyed the idea of organic qualities of glitches—in a sense that they reveal “the guts” of a machine or a file. In some strange way, “Oscillonet” feels like listening to the Internet’s heartbeat. Unnerving and challenging, as one would expect the WWW’s heart to be.

“Oscillonet” is where the past and the present collide with the modern-day Internet existing within a framework of an instrument from the late 70’s, a machine so clearly not designed to handle this form of content. And yet, it does that with such grace, highlighting a skeleton of a website with green lines that normally display as waveforms. Translating contemporary web contents into the visual and sonic language of old hardware turns “Oscillonet” into a unique artifact of media-archaeology.

We now navigate an entirely different online realm. A realm of exploitation of privacy and emotional stimuli as well as time, energy, and finances of its users. Technology is marked with the flaws of the times it was birthed in, inheriting its limitations and greed. The apparent impossibility of humanity’s dream of a better world is prominent in how often in all kinds of media utopian fantasies degrade into horror. In a world that’s increasingly structured by capitalist logics, the prospect of escape feels more futile with each passing day. What is the price one must pay for safety and comfort? What are our options?

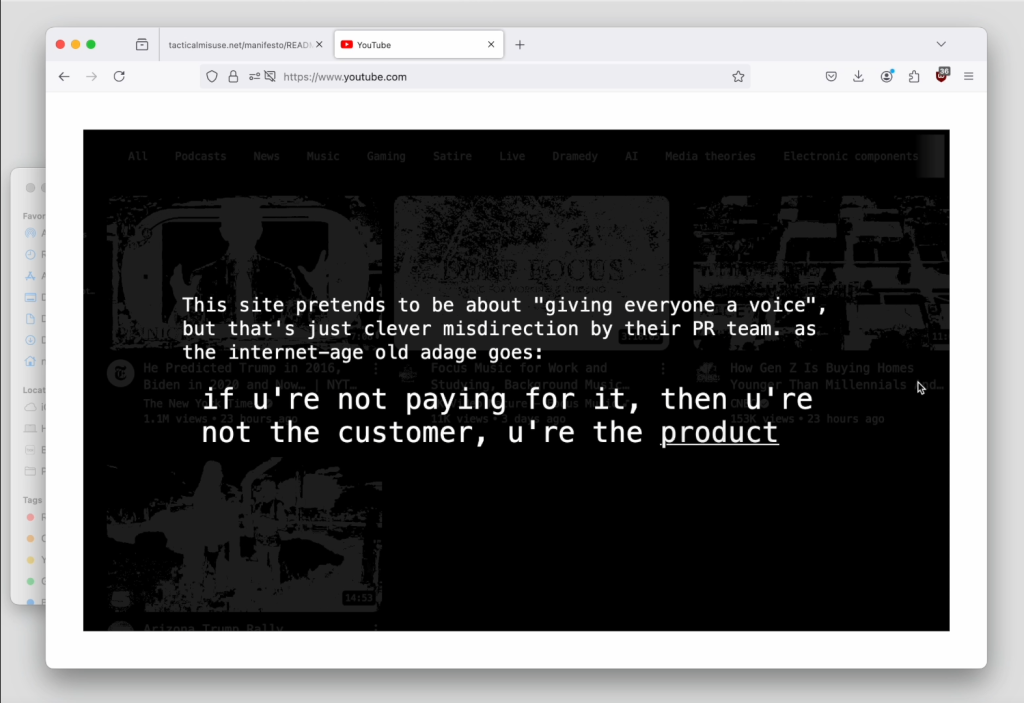

Nick Briz is an internationally-acclaimed new media artist whose work delves into the exploration (and exploitation) of digital and online technologies. “The Tactical Misuse Manifesto” is an experimental browser add-on that aims to educate on the various strategies and algorithms used to surveil, manipulate, and collect data from users. It introduces and encourages an alternative way of interacting with online platforms through the creative “misuse” of the browser’s developer tools.

Upon download and installation, the user is guided to visit a surveillance capitalist platform of their choice (Google, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, etc.) where they will be greeted with a new banner. Upon clicking on it, the website turns black and white and a new pop-up emerges explaining the various methods of exploitation and manipulation that the website utilizes.

What Web2 websites have in common is the ideology that user-generated content comes first. Briz warns us that is merely a facade and nothing more than a PR strategy. Designed to captivate our attention, these websites profit immensely from every minute we spend on them. All behaviors are measured, not just clicks. The algorithms learn our patterns and adjust and modify them to ensure we become reliant on these platforms. But Briz reminds us that the Internet itself isn’t owned by corporations and there are ways in which we can protect ourselves and reclaim our agency. The add-on then proceeds to explain how to modify websites with the use of Web Developer Tools.

Aside from being an educational tool, the add-on also treats us to a beautiful glitchy spectacle when we first launch it. There is something oddly satisfying about seeing your Instagram feed disintegrate into an unclickable abyss, but I recommend that everyone experiences it for themselves. The add-on is available for free on Chrome and Firefox and its website features a collection of scripts one can use to enhance their online browsing experience.

I quickly learned that some of these websites refuse to work when subjected to the Tactical Misuse treatment (especially when I mess with their sponsored posts). Errors started to pop up and I was no longer able to scroll down. My tactical misuse operations rendered the platform unusable. Somehow, this did not feel like a bad outcome.

A similar approach to browser-based interventions is evident in the work of Joana Chicau, a.k.a. joana.art, as she presents us with a collection of gifs of modified popular web pages. Originally a 2018 live coding performance and collaboration with Jip de Beer, Web Choreographies alters websites’ appearances through coding, diving into their architecture and breaking it down bit by bit. Through this process, a new aesthetic experience emerges disrupting what is usually a seemingly static environment of a website.

Chicau’s background in dance becomes apparent in her work as she interweaves web programming with choreography. Many of her projects combine choreographic framework and computational tools introducing new movements and shapes into the structure of a website forcing it outside its fixed grid. Again, it becomes apparent that none of these platforms were meant to be viewed this way. Web architecture prioritizes readability and clarity. Scrolling through the Internet has turned into a mundane, predictable task. Anything that interrupts this process is considered “bad design” and any form of creativity is actively discouraged in Web Developer Tools. Of course they don’t want the viewers to mess with it, as it’s by messing with it that we educate ourselves on the tools of control that these websites utilize. Thus the introduction of dynamism, of choreography, of a code-dance becomes an act of protest and emancipation. Chicau reminds us that how we move through digital space determines what that space can mean.

In a world where found objects are a well established and documented form of art production, experimental digital art still finds itself in a position where it needs to be justified or defended. Of course, this sentiment is nothing new in the art world, as Susan Sontag already wrote in her 1964 essay “Against Interpretation”: “The fact is, all Western consciousness of and reflection upon art have remained within the confines staked out by the Greek theory of art as mimesis or representation. It is through this theory that art as such (…) becomes problematic, in need of defense.” There is an expectation for art to be interpretable and when it does not offer its own interpretation, it is interpreted anyway. We cling onto the idea of confining art in easy-to-interpret and understandable categories and meanings, instead of letting it be its own thing—not in a l’art pour l’art sense, as I don’t believe art can be completely stripped off of its moral and political implications, but rather allowing art to speak for itself through itself, letting it be its own language and establish its own meanings.

In interpretation’s defense, while art encapsules the spirit of the time it was produced in, it can be hard to view it solely through the lens of that time and historical context as we recognize that there is knowledge and wisdom to be gained from it. “This is how things used to be”, says art. It’s a warning, a piece of advice, a cautionary tale. An act of creation is an act of archiving. Even for an artist, on a strictly personal level, regardless of their skillset, style, or intentions, artistic expression provides a sense of perspective when they eventually sit down to view and analyze their past work. We are quick to spot mistakes when we follow a linear, clear path. The best case scenario, the ideal course of action, the perfect solution in the perfect world, would be to look at one’s “mistakes” and say “Ah, I see where I went wrong here! Let’s not do that again.”

Except for glitch artists. These guys commit to committing “mistakes”.

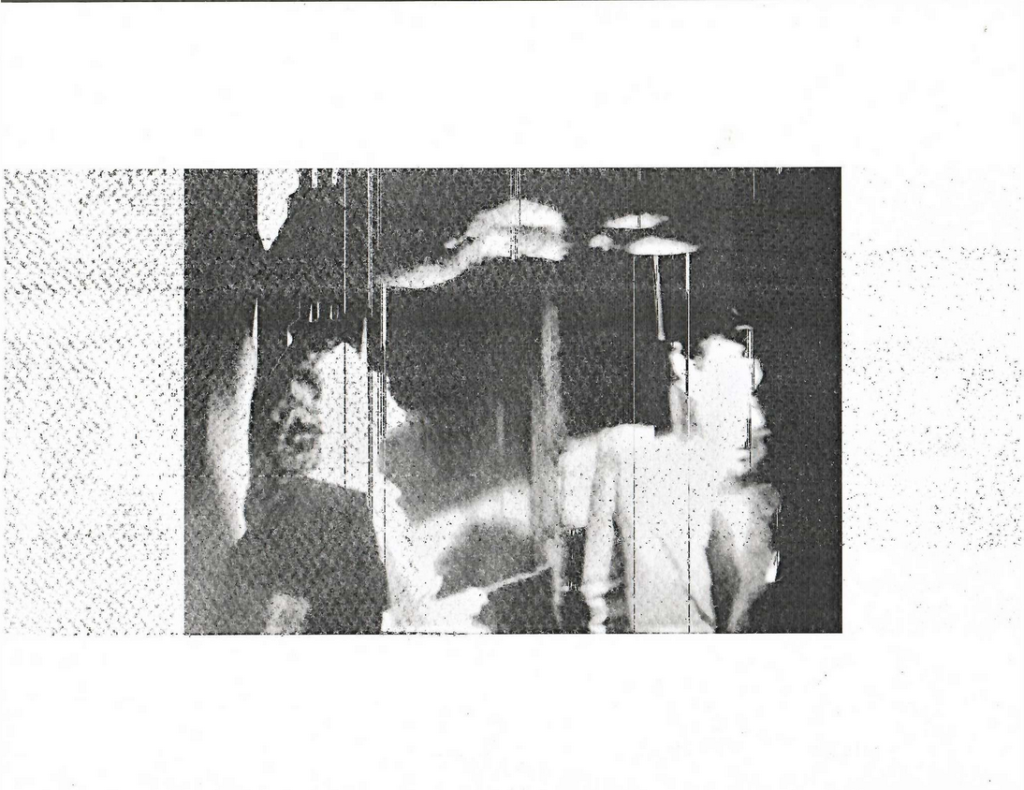

To this day—with the exception of video art and performative work—most galleries, events, and exhibitions expect artworks to be delivered to them in a physical form, even in the case of digitally-native pieces. The more “progressive” and digital-art-focused places allow screen displays if the artwork is a website or an application, but rarely provide this luxury for still images. In other words, there has to be a valid reason for an artwork to not be printed. This only contributes to the idea that “real art”, and especially art legitimized and supported by institutions, is printable and/or tangible. But glitch art is rarely created with the idea of being printed out. AK OCOL, a self-taught artist from the Philippines, explores this very concept in her work, “ghost no.7_(linger)”. Curious about how the digital and virtual spaces coincide with and influence the “real-life”/offline world, she criticizes the idea of treating glitch art like ready-to-print photographs, arguing that printing “flattens” the idea of a glitch and removes its integrity. Motivated to materialize digital noise artifacts into physical media, AK OCOL sought to incorporate glitches into the printing process with the use of incompatible materials.

The process could be considered an attempt at translating a glitch into a non-digital world and, aesthetically, the final result feels like a rough translation, a (mis)interpretation of what the digital noise is with black ink splatters trying to imitate visual artifacts. It’s still undoubtedly glitch art, but it’s strangely incomprehensible and different. Taken out of its natural habitat, the piece is rendered almost asemic for the sake of becoming a market-friendly collectible piece of art.

Asemic writing is a type of writing (or art) that mimics the appearance of a written language, but doesn’t use real words or follow any specific linguistic system. It’s not designed to be readable and conveys its messages through pure expression of shapes and symbols. There is a significant overlap between the glitch and asemic writing communities so seeing quite a few asemic pieces in the fu:bar exhibition wasn’t a surprise.

Although asemic writing doesn’t have to be (and often isn’t) exclusively digital, “Ephemeral Typing” by Charlotte Lengersdorf is a series of browser-accessible interactive writing programs in which each keystroke creates a new visual form. Lengersdorf, German artist and lecturer whose research and practice explore the intersection of typography, philosophy, and creative coding, defines asemic as “the absence or negation of meaning” and contrasts it with the action of typing, which in itself is a practice of conveying meaning.

But instead of conventional meaning, the act of typing is used to create an asemic piece of art. While interacting with “Ephemeral Typing”, I couldn’t help but try to understand how it works, despite knowing that the final product is meant to be unreadable. But once I put behind my ego-driven desire to outsmart the program, I found joy in creating these indecipherable patterns. Typing becomes an act of performance rather than a vessel for semantic transmissions. The screenshot above would say “fubar glitch festival 2024” if it was typed in any writing software, but intentions are useless and ultimately meaningless in the framework of “Ephemeral Typing”. Any attempt at understanding or reading what was written fails and thus failure becomes an expected and desired result.

In a similar fashion, “Poem for the dead” by an Australian digital artist, Bob Georgeson, is a book that can never be read or printed. In artist’s words, the book is a “neo-dada montage that tells a story of a dream that never happened”. Georgeson’s work focuses on the relevance of the themes of alienation and isolation and the impact they have on new technologies and forms of communication in a world that’s heading into its own demise at an alarming and exponential speed. And yet again, we are presented with the rejection of printability, of becoming a physical copy of a digital file. It reads less as a technical constraint and more as a manifestation of dread. Meaning erodes alongside the world it reflects.

The trajectory of challenging legibility continues in the work of Ivan Netkachev, a Georgia-based multimedia artist, theorist, and writer, who introduces us to a concept of a Procedural Essay. What is a Procedural Essay? Don’t worry about it.

Well, it is, theoretically speaking, a computer program that generates arguments in an imaginary reasoning, but Netkachev’s thesis is not interested in definition, much like a Procedural Essay is not interested in being defined or even comprehensible. The goal of the thesis is not to figure out what it is, but rather to show what it does, which is to generate meaning. Meaning, which may or may not be understandable as a Procedural Essay prioritizes calculations over language. A thought experiment for the machine which workings are as devoid of human input as possible, but never entirely nonhuman, since, all things considered, a machine is still a uniquely human invention.

Inspired by early computer art and video games, Netkachev lists games such as “Everything” (2019) and “LSD: Dream Emulator” (1998) as examples of Procedural Essays highlighting the aspects of exploration and interactivity, but also a certain lack of care for what it is that we, the explorers, think of the things that are unfolding before our eyes. As tricky as it may be to understand, a Procedural Essay is not nonsensical, although it shares some qualities with asemic writing in a way where its meaning lies in its structure and mechanics. Much like glitches, it offers a unique insight into the workings of protocols exposing their failures. Ultimately, its goal is not to trap its users in its framework, but to offer liberation through this exposure or at least that’s the encouraged approach.

When it comes to tools of creative expression, video games rarely come to mind and yet they make a potent site for experimental aesthetics. “Explaining-Showing-Doing” is a series of glitched videos captured in The Sims 4 by Estelle Flores, a Brazilian contemporary artist who uses simulation games to create artistic machinimas. Her work explores the meaning of the word “play” bringing out the performative aspects of gaming.

The distorted black and white aesthetic of these videos distances itself from the game’s original appearance, creating an eerie and haunting experience. Yellow text appears with vague, ominous statements, but occasional pop-ups with the game’s UI remind the viewer that, yes, this is still a worldwide-known video game, The Sims.

Play can be a struggle for artists because more often than not we’re under the impression (or rather forced into the way of thinking) that pain or suffering constitutes “real art” and that “real art” can only be achieved through the use of tools specifically designed for art creation. Flores does not care for this mindset as she asks the following questions: “Who do I want to be? What do I want to do?”. Her art is not afraid to reference itself as it exists within the medium of a video game, it seems to understand its own confinements well enough to expose/explore the existentialism within. What does it mean to exist within a system not built for existence? What is autonomy in a predetermined world? The irony and beauty of performing these explorations within the framework of a life simulator is not lost on me.

While all of the work presented flirts with the theme of failure in a variety of ways and from multiple different perspectives, there is a tendency among artists to reject the idea that a glitch is a mistake and to embrace its beauty and poetry as if a glitch occurrence was destined to happen. Sometimes, a failure or a mistake, happens so suddenly, so smoothly, and quietly, it’s hard to consider it an unnatural occurrence.

I brought up found objects earlier. I did so specifically because I think it shares some similarities with glitch art. While I’m not a huge supporter of the theory that the only true glitches—or “pure glitches” as Shay Moradi prefers to call them in the 2004 dissertation “Glitch Aesthetics”—are found glitches, they are, without a doubt, still glitch art and a crucial part of what glitch art is and how it came to be in the first place.

Truth is glitches can happen to anyone! Daria Ivans, a xenomedia artist from Russia, warns us of this reality as xe presents us with a collection of images, appropriately titled “unfully_recovered”, that glitched out as a result of recovering files after “something went wrong” with a cleaner app. The artist reflects on being a mere observant of the process and how the glitches did not depend on xyr intentions and came to exist seemingly on their own volition. Sure, there had to be a certain set of circumstances that led to it happening, perhaps such a thing can be investigated and recreated to some extent. But there is a certain rawness that stuns the witness begging the question: is the artist even necessary here? Does glitch art create itself?

In another example of things taking an unexpected turn, “Glitch Paca” by a Guatemalan artist, g1ft3d, we’re presented with a selection of failed 3D projects that show corrupted files in Blender. The artist’s brief description of the artwork does not fail to mention the frustration these glitches have caused that’s apparent in the way the artist tries to navigate the destroyed 3D objects as the chaos continues to unfold. In “Unmoored”, a short video by a Washington-based artist Chris Combs, the camera slowly begins to drift away with the flow of the water, leaving the artist perplexed, worried, but, hopefully, a little bit amused. Things just like to take over, unbothered by our humanly predispositions; our time pressure, plans, or feelings.

We took a look at what is merely a small fraction of fu:bar 2024 curatorial selection. There is much, much more to explore as the festival continues to put emphasis on showcasing a wide variety of artists and glitch techniques. With all the diversity of play and experimentation on display, one question remains. The biggest enemy of every glitch artist, the forbidden combination of words, the one that always inevitably follows the statement “I do glitches”, the dreaded question…

What is glitch art?

Ok, so what’s the big deal? Why do glitch artists hate this question so much? Admittedly, at this point it is mostly an innocent meme, a little inside joke derived from countless online debates on what constitutes a glitch and its seemingly ever-expanding description that, as we move forward, only seems to include more and more diverse forms of creative expression. It eventually became a sort of an umbrella term. Our inability to define glitch art relates to its decentralization and multiplication. While it can be a philosophy, a community, an art movement, a technique, it is also, simultaneously, none of these things.

But today, I would like to offer a new meaning: glitch art is death.

Not dead, but it is death itself. A resistance to life, not as an abstract or metaphysical concept, but to life as a set of imposed structures we were thrown into at birth. But with death comes transformation. A new reality, a new form of being (or not-being), a new meaning. Glitch art is simply a natural consequence of the world we live in, a world in which definitions become blurred, words seem to lose meaning, language barriers cease to exist with the immediate accessibility of translation tools. It serves to repurpose, alter, interrupt, distort, reshape, and transform.

This year is a transformative period for the fu:bar festival as it changes its structure into a biennale. Coincidentally, the Ministry of Culture made the decision to cut the funds for the festival (and many other programs) and rejected the appeal. While the motivation behind this verdict remains in the land of speculation, its effects are most certainly destructive (and not in a “fun” glitchy way). The fu:bar festival has secured Zagreb on the international map of glitch art as THE glitch hotspot. As somebody who had the privilege of attending the event in-person multiple times, I can confirm it’s not just reflected in the fact that hundreds of artists apply to the festival every year, but also in its success as an URL+IRL event with participants planning their travel to Croatia months in advance. Even after lockdowns caused by COVID-19 and a devastating earthquake that forced the fu:bar team to move to a different venue as the previous one was rendered hazardous, the festival managed to pull through and reemerged with artists from different countries and continents flocking back to Zagreb to exchange experiences, knowledge and bond over their passion for glitch art, a form of art production so niche yet so widely spread there is no confusing it for anything else.

Glitch isn’t just a technique and you truly get to observe it when you participate in events like fu:bar where you meet dozens of people from a variety of different backgrounds and you learn how every single one of them shares some form of a unique bond with the concept of brokenness. Glitches attract glitches.

At the risk of being accused of being overly melodramatic, to be an artist is to be broken, because to be human is to be broken, and the act of creation is essentially peak humanity. I think that, of all people, glitch artists seem to understand it excruciatingly well. While the landscape of glitches changes with continued technological development, the mystifying nature of mistakes lures us in. In the brokenness, we find beauty and solace. And we repurpose it, and alter, and interrupt, and distort, and reshape, and transform.

“Life’s a glitch, then you die.”

Addendum:

An extra paragraph that I ended up scratching from the final text after months of rewriting it…

To fully understand the work we’ll be diving into, we must first define or attempt to define the meaning of failure, which isn’t a particularly easy task, especially for a glitch artist. The longer one dabbles in glitch, the blurrier the line between failure and success becomes. Not to mention a glitch artist’s natural aversion to definition itself (this is only partially a joke and a reference to the universally dreaded question of “what is glitch art”, which, hopefully, we won’t be focusing on today).

… Whoops!

Collection & text: Ras Alhague

Fubar curatorial collections are a part of the /’fu:bar/ 2024 Glitch Art Exhibition program.